Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992, on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora, urges EU member states to promote the management of parts of the landscape which are of paramount importance to wild fauna and flora. These are areas that, due to their linear and continuous nature (such as rivers and their banks or the traditional demarcation systems of fields), or their role as linking points (such as ponds or thickets) are essential for the migration, geographical distribution and genetic exchange of wild species.

In Spanish legislation, Law 42/2007 of 13 December, on Natural Heritage and Biodiversity. Official State Gazette 299, 12/14/2007 (amended by Law 33/2015, Official State Gazette 227, 11/22/2015) defines ecological corridor as: “an area of variable size and configuration which, due to its position and its state of conservation, functionally connects natural spaces of particular importance for wild flora or fauna which are separated from each other, allowing, among other ecological processes, genetic exchange between populations of wild species or the migration of specimens of those species” (Law 42/2007. Art. 3).

Similarly, Portuguese legislation covers the concept of “areas of continuity”, in Article 5 of the “Legal Regime for Nature and Biodiveristy Conservation”, Decree-Law (DL) no. 142/2008 of 24/07 (modified by Rect. no. 53-A/2008 of 22/09, DL no. 242/2015 and DL no. 42-A/2016 of 12/08). Specifically, these areas of continuity, which include the Dominio Publico Hídrico (Public Waterways), would be those that “establish or safeguard the linking and genetic exchange of populations of wild species between different core conservation areas, contributing to the adequate protection of natural resources and to the promotion of spatial continuity, the ecological coherence of classified areas and the connectivity of biodiversity components throughout the territory, as well as the appropriate integration and development of human activities“.

The preservation of connectivity and the ecological integrity of the Natura 2000 Network of nature areas is a legal requirement of the Habitats Directive and Law 42/2007. Both acts stipulate the importance of ecological corridors as elements of unity between areas of outstanding environmental value, those considered core areas of biodiversity, including protected areas, as well as areas which, though not legally designated as protected, are home to outstanding biodiversity.

Of the different types of ecological corridors found in the north-west of the Iberian peninsula (mountainous, river, coastal and marine), it is the river corridors which most effectively allow the refuge, movement and dispersal of a large number of wild species, belonging to different taxonomic groups and to different types of environment (terrestrial, semi-terrestrial, aquatic), also serving as an effective link, connecting montane corridors and core areas of biodiversity with coastal and marine conservation areas.

The concept of river corridor goes hand-in-hand with the concept of the river itself, which is far more than a mere mass of water flowing along a riverbed. The river corridor covers the whole of the river’s territory; that is, the river in its low-water channel, the riverbank vegetation and the floodplain, together with the vegetation cover associated.

In addition to their intrinsic ecological value, river corridors fulfil two basic functions, as ecological connectors and as hydrological regulators.

In terms of ecological value, river corridors are home to ecosystems associated with the river, both aquatic and terrestrial, as well as those in between, forming an area of outstanding biodiversity which functions as a refuge for many species that live in the river environment. This ecological value has led to the declaration of numerous Nature Protection Areas, particularly within the Natura 2000 Network, considering the habitats and species of community interest found in them.

This unique ecological value is increased by the basic function of river corridors as ecological connectors between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and between areas of outstanding environmental value that are distant from each other. This function is particularly important given that terrestrial ecosystems are very fragmented by infrastructure and various land uses. In this context, river corridors are the most robust connectors, or at least the most functional, for interconnecting populations of living beings that would otherwise be isolated.

Finally, in their role as hydrological regulators, river corridors control the water level and the sediment loads carried by the river when it floods, dissipating part of its energy, limiting the consequent damage and recharging the aquifers. In this way, the river transports both sediments to beaches and nutrients to estuaries and coastal waters, providing the ecological and economic benefits associated.

A river corridor includes various ecological environments. Firstly, there are the free-flowing water environments which make up the river course; in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, these environments can be categorised as two types of habitat of community interest: 3260 Water courses of plain to montane levels with the Ranunculion fluitantis and Callitricho-Batrachion vegetation and 3270 Rivers with muddy banks with Chenopodion rubri p.p. and Bidention p.p. vegetation

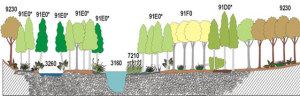

Beyond the river course, under natural conditions, the banks and the floodplain are made up of different types of habitat. The gallery or riparian forests are categorised as priority habitat type 91E0* Alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior (Alno-Padion, Alnion incanae, Salicion albae), designated variously according to the dominant tree species: alder, ash, willow, birch, hazel, etc., and located in contact with the river. Further from the river course, we move into different types of arboreal biocoenosis adapted to flood and moist soil conditions – alluvial forests of birch and ash trees – which are also categorised as priority type 91E0*. Near some rivers there are small areas of mixed oak, elm and ash forests which correspond to habitat 91F0 Riparian mixed forests of Quercus robur, Ulmus laevis and Ulmus minor, Fraxinus excelsior or Fraxinus angustifolia, along the great rivers (Ulmenion minoris).

Together with the arboreal habitats, the river corridor may also contain areas of hygrophilous herbaceous vegetation (6410 Molinia meadows on calcareous, peaty or clayey-silt-laden soils (Molinion caeruleae), 6420 Mediterranean tall humid herb grasslands of the Molinio-Holoschoenion, 6430 Hydrophilous tall herb fringe communities of plains and of the montane to alpine levels), as well as small wetlands, categorised as freshwater environments (3110 Oligotrophic waters containing very few minerals of sandy plains (Littorelletalia uniflorae), 3120 Oligotrophic waters containing very few minerals generally on sandy soils of the West Mediterranean with Isoetes spp, 3130 Oligotrophic to mesotrophic standing waters with vegetation of the Littorelletea uniflorae and/or Isoeto-Nanojuncetea, 3140 Hard oligo-mesotrophic waters with benthic vegetation of Chara spp, 3150 Natural eutrophic lakes with Magnopotamion or Hydrocharition-type vegetation, 3160 Natural dystrophic lakes and ponds), wet scrublands (4020* Temperate Atlantic wet heaths with Erica ciliaris and Erica tetralix) and bogs (91D0* Bog woodland, 7110* Active raised bogs, 7140 Transition mires and quaking bogs, 7150 Depressions on peat substrates of the Rhynchosporion, 7210* Calcareous fens with Cladium mariscus and species of the Caricion davallianae).

There is often contact between the river corridor and climax forests, through oak woods (9230 Galicio-Portuguese oak woods with Quercus robur and Quercus pyrenaica) and other types of climax forests, while contact with the marine environment is through estuaries (1130 Estuaries) and their associated marshes (1310 Salicornia and other annuals colonising mud and sand, 1320 Spartina swards (Spartinion maritimae), 1330 Atlantic salt meadows (Glauco-Puccinellietalia maritimae), 1420 Mediterranean and thermo-Atlantic halophilous scrubs (Sarcocornetea fruticosi).

As a consequence, the river corridors of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula are home to a total of 25 of the habitat types in Annex I of Directive 92/43/EEC, representing 35% of the total habitat types of the territory, and 11% of the total habitat types of the entire European Union. These figures are very important, especially taking into account that these corridors are usually located along the courses of river channels and, therefore, the territory they occupy is proportionally reduced compared to other types of habitat. The presence and distribution of such a high diversity of the habitats in Annex I of Directive 92/43/EEC has prompted a huge number of Natura 2000 sites to be designated in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, in order to guarantee their being maintained or restored to a favourable state of conservation.

The following table shows the types of habitat present in the river corridors of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. For each one, there is a link to a description, according to the Interpretation Manual of EU Habitats, which has been translated into the “Manual of Habitats of Galicia” by the Institute of Agricultural Biodiversity and Rural Development (IBADER) of the Campus Terra of the University of Santiago de Compostela. Included in each file are the habitat’s diagnostic features, typical species, areas of distribution and presence, pressures and threats, state of conservation, other associated habitats, etc.

HABITAT FILES | ||

1130 | Estuaries | |

1310 | Salicornia and other annuals colonising mud and sand | |

1320 | Spartina swards (Spartinion maritimae) | |

1330 | Atlantic salt meadows (Glauco-Puccinellietalia maritimae) | |

1420 | Mediterranean and thermo-Atlantic halophilous scrubs (Sarcocornetea fruticosi) | |

3110 | Oligotrophic waters containing very few minerals of sandy plains (Littorelletalia uniflorae) | |

3120 | Oligotrophic waters containing very few minerals generally on sandy soils of the West Mediterranean with Isoetes spp | |

3130 | Oligotrophic to mesotrophic standing waters with vegetation of the Littorelletea uniflorae and/or Isoeto-Nanojuncetea | |

3140 | Hard oligo-mesotrophic waters with benthic vegetation of Chara spp | |

3150 | Natural eutrophic lakes with Magnopotamion or Hydrocharition-type vegetation | |

3160 | Natural dystrophic lakes and ponds | |

3260 | Water courses of plain to montane levels with the Ranunculion fluitantis and Callitricho-Batrachion vegetation | |

3270 | Rivers with muddy banks with Chenopodion rubri p.p. and Bidention p.p. vegetation | |

4020* | Temperate Atlantic wet heaths with Erica ciliaris and Erica tetralix | |

6410 | Molinia meadows on calcareous, peaty or clayey-silt-laden soils (Molinion caeruleae) | |

6420 | Mediterranean tall humid herb grasslands of the Molinio-Holoschoenion | |

6430 | Hydrophilous tall herb fringe communities of plains and of the montane to alpine levels | |

7110* | Active raised bogs | |

7140 | Transition mires and quaking bogs | |

7150 | Depressions on peat substrates of the Rhynchosporion | |

7210* | Calcareous fens with Cladium mariscus and species of the Caricion davallianae | |

91D0* | Bog woodland | |

91E0* | Alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior (Alno-Padion, Alnion incanae, Salicion albae) | |

91F0 | Riparian mixed forests of Quercus robur, Ulmus laevis and Ulmus minor, Fraxinus excelsior or Fraxinus angustifolia, along the great rivers (Ulmenion minoris) | |

9230 | Galicio-Portuguese oak woods with Quercus robur and Quercus pyrenaica | |

River corridors are one of the main reserves for the diversity of wild species of flora and fauna in our territories. River environments, which comprise both the flowing waters and the ecosystems of the riverbanks and floodplains, allow the existence of species typical to these environments, which cannot be found in other environments, hence giving river corridors a strategic role. when it comes to determining the conservation of those species. In the specific case of the stretches of river in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, they are probably the best examples of alluvial and gallery forests on the Iberian Peninsula. Some of the riparian forests are home to more than 60 species typical to nemoral environments, showing the important role they play as a habitat for a rich and abundant diversity of flora species, but also of fauna. Among them, it is worth highlighting a wide range of species that are considered to be of interest for conservation, which is why they have been included in the annexes of the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) and the Birds Directive (2009/147/EC), as well as in the national and regional conservation catalogues of Spain and Portugal.

Among the flora of the river corridors, three species of fern should be mentioned, which are of interest for the conservation of biodiversity and have been included in Annexes II and IV of Directive 92/43/EEC: the woolly tree fern (Culcita macrocarpa), the Killarney fern (Vandenboschia speciosa) and the chain fern (Woodwardia radicans). These species are considered paleotropical relicts that have remained in Atlantic regions of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, which reinforces their status as elements of great interest for the conservation of the region’s natural value. Other important ferns are Isoetes fluitans, an aquatic indicator species of oligotrophic and well oxygenated waters, which has been classified as Endangered in the Galician Catalogue of Endangered Species (Decree 88/2007), as well as Dryopteris aemula and Dryopteris guanchica, pteridophytes present on riverbanks that have been classified as Vulnerable in Galicia, or Dryopteris corleyi, of Special Interest in Asturias.

Mosses and lichens are also well represented groups in river corridors, with some aquatic species of interest, as well as many others that live in trees (epiphytes) and rocky outcrops on the riverbanks. Among the clear examples are Hamatocaulis vernicosus (included in Annex II of Directive 92/43/EEC), Leptogium cochleatum, which has been classified as Endangered, or the Vulnerable species Cephalozia crassifolia, Chiloscyphus fragrans, Cryphaea lamyana, Cyclodictyon laetevirens, Fontinalis squamosa, Lepidozia cupressina, Metzgeria temperata, Pseudocyphellaria aurata, Radula holtii, Schistotega pennata, Telaranea nematodes and Ulota calvescens.

Notable among the angiosperms of interest for conservation which are present in river corridors are the narcissus species (Narcissus cyclamineus, Narcissus pseudonarcisusus nobilis, Narcissus triandrus), as well as the aquatic species Luronium natans, all of which are included in Annexes II and IV of Directive 92/43/EEC, and the hygrophilous Cyperus Rhynchospora modesti-lucennoi (classified as Threatened by the IUCN). Among the remaining species, it is worth mentioning Callitriche palustris and Nymphoides peltata, classified as Endangered in Galicia, as well as Cardamine raphanifolia gallaecica and Carex hostiana, Vulnerable in Galicia, Thelypteris palustris, Vulnerable in Asturias, and Carex vesicaria, found in Lagoas de Bertiandos and one of only two populations in Portugal.

Among the animal species of interest which are associated with river corridors, invertebrates are undoubtedly an important group. Perhaps one of the orders most common to river corridors is that of odonates, since their nymphal stage is aquatic, while for the rest of their life cycle, they are found on riverbanks. In the river corridors of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, Macromia splendens, Oxygastra curtisii, Gomphus graslinii and Coenagrion mercuriale are found, all being included in Annex II of Directive 92/43/EEC (additionally, the first three are also included in Annex IV of Directive 92/43/EEC); Macromia splendens is considered Endangered, while Oxygastra curtisii has been classified as Vulnerable. Aquatic bivalve molluscs are also important in river corridor environments, in particular Margaritifera margaritifera (included in Annex II of Directive 92/43/EEC, classified as Endangered), and Unio delphinus (classified as Vulnerable in Galicia). Among freshwater crustaceans, the crab Austropotamobius pallipes stands out, included in Annex II of the Directive 92/43/EEC and classified as Endangered in Galicia. Other invertebrate species of community interest (included in Annex II of Directive 92/43/EEC) which are present in river corridors, and whose presence and need for conservation have been taken into account when designating and demarcating Natura 2000 sites, are the snail Elona quimperiana, the slug Geomalacus maculosus, the beetle Lucanus cervus and the butterfly Euphydryas aurinia.

The presence in river corridors of fish species of interest for conservation is indicative of the value of river corridors for the conservation of natural resources and biodiversity. Migratory species are especially noteworthy, indicating the importance of river corridors for the migration, geographical distribution and genetic exchange of wild species. These include Alosa alosa, Alosa fallax, Petromyzon marinus and Salmo salar, all of which are included in Annex II of Directive 92/43/EEC, and not forgetting the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) a catadromous migratory species with a complex biological cycle, classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List. In addition, other species are found in the middle reaches, such as Achondrostoma arcasii, Pseudochondrostoma duriense (included in Annex II of Directive 92/43/EEC) and Gasterosteus aculeatus (classified as Vulnerable in Galicia).

Amphibians are species closely associated with rivers, due to the total or partial linking of their life cycle to aquatic environments. Among the amphibian species of interest for conservation that are common to river corridors, those included in Annex II of Directive 92/43/EEC should be highlighted (Chioglossa lusitanica, Discoglossus galganoi), as well as a vast number of species included in the various catalogues of threatened species, classified as Vulnerable (Alytes obstetricans, Hyla molleri, Lissotriton boscai, Lissotriton helveticus, Pelobates cultripes, Pelodytes punctatus, Pelophylax perezi, Rana iberica, Rana temporaria, Salamandra salamandra, Triturus marmoratus).

Reptiles are also present in river corridor environments, both species with aquatic habitats and those that live in riparian areas. Among the former, it is possible to cite the presence of Emys orbicularis (included in Annexes II and IV of Directive 92/43/EEC and classified as Endangered in Galicia) and Mauremys leprosa (included in Annexes II and IV of Directive 92/43/EEC), as well as Natrix maura and Natrix natrix (included on the Spanish List of Wild Species under Special Protection). With regard to the reptile species that can be found on riverbanks, those included in Annexes II and IV of Directive 92/43/EEC should be noted, such as Iberolacerta monticola or Lacerta schreiberi, and others that have been catalogued, such as Zootoca vivipara (classified as Vulnerable in Galicia).

Birds are the group of vertebrates with the highest number of taxons of interest for conservation in the river corridors of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. Among the species in Annex I of Directive 2009/147/EC (whose presence determines the demarcation of the Natura 2000 Network’s Special Protection Areas for Wild Birds), those recorded in this region include Alcedo atthis, Ciconia ciconia, Egretta alba, Falco pereginus, Himantopus himantopus, Ixobrychus minutus, Milvus migrans, Nycticorax nycticorax, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and Tringa glareola. However, species included in the various catalogues are also present, such as Emberiza schoeniclus lusitanica, Gallinago gallinago, Numenius arquata, Phalacrocorax aristotelis and Vanellus vanellus, as well as species included on the Spanish List of Wild Species under Special Protection, such as Acrocephalus arundinaceus, Ardea cinerea, Cinclus cinclus, Delichon urbica, Erithacus rubecula, Falco subbuteo, Hirundo daurica, Jynx torquilla, Limosa limosa, Muscicapa striata, Otus scops, Phylloscopus collybita, Riparia riparia, Saxicola torquata or Tringa ochropus, among many others.

River corridors are also home to mammals of interest for conservation, included both in the annexes of Directive 92/43/EEC and in the different national and regional conservation catalogues of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. Among aquatic mammals, the presence of Galemys pyrenaicus and Lutra lutra (included in Annexes II and IV of Directive 92/43/EEC) has been cited, the former having been classified as Vulnerable in Spain. Among the mammals present on riverbanks, the order Chiroptera should be highlighted, which includes several protected species of bat (Eptesicus serotinus, Myotis daubentonii, Nyctalus neisleri or Rhinolophus hipposideros), as well as other species of riparian habitats that have also been catalogued, such as Felis silvestris or Mustela erminea.

The presence of such a high diversity of species in the river corridors of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula has prompted a huge number of Natura 2000 sites to be designated (Sites of Community Interest, Special Conservation Areas, and Special Protection Areas for Wild Birds), in order to guarantee their being maintained or restored to a favourable state of conservation.

Numerous components of the material cultural heritage that have been conserved in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula are associated with river corridors, especially in the basins and sub-basins where the LIFE Fluvial project operates. The best examples are ancient human settlements which were strategically located close to river corridors, for the provision of water, fish, wood and fodder. From these ancient sites, towns and cities would later emerge, the urban development taking place on many occasions in the river corridors themselves.

The use of a river’s current to drive various devices also goes back to ancient times, when different types of mills, fulling hammers, mallets and ironworks were operated in this way. These devices are based on the use of kinetic energy from the current, converted to mechanical energy to allow the grinding of various materials (particularly cereals), the transformation of different types of fabrics, the moulding of iron pieces, the polishing and sharpening of tools, the turning of wooden parts, and so on. In short, these ingenious traditional systems were adapted to the conditions of the river environment, to the technical knowledge of the time and to the demands of local markets.

Another cultural element of great importance is bridges, the oldest of which are associated with the arrival of the Romans, although many were built and rebuilt in later times, during the Middle Ages or the Modern Age, and still exist today alongside bridges built in a contemporary style. There are also bridges that are less monumental, built to meet the needs of local populations, either made entirely of stone or of stone combined with wood. Related to these bridges, the word “Puerto” (port) is still found in many place names, indicating where the river was forded, either with the help of small boats or crossing with cars or horses.

Now an ethnographic feature, river boats were, until the second half of the 20th century, an essential means of communication for transporting people and goods. In some sub-basins, such as the upper basin of the Minho river, a traditional vessel (the batuxo) has been used as a sustainable tool for the removal of invasive alien species from the river channel. This has made it possible, firstly, to recover and promote the ethnobiological heritage of the region, and secondly, to begin the conservation of our natural heritage without using mechanised tools or motor boats, a method that is not aggressive towards the aquatic environment.

Equally associated with the presence of river corridors, it is possible to identify numerous fountains that are now a fixture of popular culture. Their construction styles are quite varied, from simple water pipes to structures of great sophistication. Fountains are often closely linked to popular culture and legends (apparitions and miraculous occurrences, healing powers, etc.), although they also have an important historical and artistic value.

The abundance of fish also saw the creation of all kinds of gadgets designed to catch them. Harpoons, arrows and nets were used skilfully by the ancient settlers, which led to the rise of fisheries. Some authors have connected the emergence of this practice with Romanisation, although there is no reliable data to support this, so they could be of later origin, possibly from the Middle Ages, when they are documented in different archives. Fisheries were generally located on a rocky outcrop on the riverbed, on which V-shaped walls were built to force the water and the fish inside, directing them into small funnels where the nets were attached. This type of fishing was a long way detached from any criterion of sustainability, supplying as it did a significant amount of fish to the fishery owner, who was generally a nobleman or clergyman.

Equally important is the river-themed intangible heritage that has been preserved, centred around the basins in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. Local legends, fables and stories share common elements with those of other Iberian and European regions, but there are also unique and distinct elements found nowhere else. Also, various uses, performances, knowledge and techniques related to our river corridors, including the instruments, artifacts and spaces inherent to them, have been passed down from generation to generation and, for each river, recreated the people’s relationship with the aquatic environment and the history of the territory that surrounds them, giving the land its own sense of identity, in which the river corridor acts as a link and catalyst that evokes secular traditions.

River corridors, and especially the rivers themselves, were and still are the inspiration for many writers and artists. Alvaro Cunqueiro (1911-1981) referred to Galicia as the “country of a thousand rivers”, while the various poems of Manuel María Fernández Teixeiro (1929-2004) are odes to the Minho river, the Pais dos Rios Galegos (Country of Galician Rivers), and the river courses of the Terra Chá (Upper Basin).

Meus amadisimos peixes, ordenados en tribos, provincias e naciós: salmós, troitas, anguías, escalos, sábalos, lampreas e ainda o recente blas-blas… Morades en casais, parroquias, vilas e cidades que os humanos non ollan nin descobren: só a vós vos falo pois quero sementar no voso leve e delicado corazón a flor marabillosa do amor. Coidade dos fondos subacuáticos e non deixedes luxar endexamais a pureza das augas cristalinas. | Confederádevos xa coas galiñoas, cabaliños do demo, parrulos, arceas e lavancos: loitade ferozmente contra tanta polución envelenada que vos asasina sin piedade e destrúe a beleza dos ríos e a perfecta fermosura do mundo. Defendede ata a morte o voso reino: ¡fuxide das mortíferas nasas, das invisibeis, enganosas redes, das cordas, dos anzois, da dinamita e habitade en paz eternamente a marabillosa luz das ondas libres! |

Manuel María Fernández Teixeiro: O MIÑO canle de luz e de néboa. Poem: Proclama os peixes do Miño | |

River corridors are not only fundamental to the short- and long-term safeguarding of biodiversity, but are also multi-purpose spaces capable of providing valuable benefits to humans, which directly and indirectly affect our (quality of) life. In fact, human beings are an integral part of these systems. Ecosystem services, as they are known, are the benefits that river corridors provide to us, such that their ecological and environmental status and functioning translate into a large number of goods and services, usually classified as provisioning, regulating and cultural.

Forest ecosystems, particularly the hygrophilous forests associated with riverbanks and the tail ends of estuaries, together with aquatic ecosystems, form the heart of the river corridors in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. In fact, humid forests include the most important habitats within the LIFE Fluvial project and are of great importance for the conservation of biodiversity, which, in turn, is the source of many goods (wood and firewood, genetic resources, etc.); as such, changes to the biodiversity found in these forests will influence the supply of ecosystem services provided to society.

The regulating services are, without doubt, the most important ecosystem services provided by the entire river system. Of particular note is the regulation of the ecological system’s self-purification capacity (including regulating air-water-soil quality, the hydrological cycle, climate change and the nutrient cycle) and biological regulation (regulating pests), which is particularly important for human health. In addition, they provide other services related to the life cycles of these environments (nursery of species, provision of habitat) and their capacity to buffer floods and storms. With regard to provisioning or supply services, these ecosystems currently provide water, of quality and in vast quantities, for urban uses (residential, commercial, industrial, public) and other uses such as agricultural, energy production or leisure (bathing, recreational fishing, etc.), as well as wood and firewood. In terms of cultural services, aquatic ecosystems are used intensively for fish farming, proving the excellent state of their water and, therefore, of the fish populations that live in them; meanwhile, the forest ecosystems found on the forested banks along the river courses fulfil a wide range of functions related to the enjoyment of open-air leisure pursuits, aesthetic and landscape improvement in the vicinity of populated areas, sports and nature tourism, birdwatching, environmental education and interpretation, and cultural heritage historically associated with these systems.

On occasion, the overexploitation or intensification of certain provisioning services or the unsustainable use of certain cultural services associated with the public use of the river system have caused a decline in the provision of regulating services and in the levels of biodiversity found in the region. For example, irresponsible practices in the extraction of wood can have serious effects on the conservation status of wooded ecosystems. The intensification of the use of riverbanks, destroying natural habitats (riparian forests, tall herbs, etc.) to make way for reforestation for the purposes of productivity or pasture for food production, significantly harms the natural values of river corridors. Likewise, the destruction of natural habitats to set up recreational facilities and infrastructure (bathing, river beaches, recreational areas, etc.) also entails a negative impact on the regulating capacity of the river corridor, and consequently the provision of this type of ecosystem services. Meanwhile, excessive fishing and the construction of obstacles for different purposes contribute to the decline in the populations of different fish species. In short, the promotion of cultural or provisioning services cannot be at the expense of the multi-functionality of these systems, or harm the regulating services (keys to our welfare, public safety and health), nor cause an accelerated loss of the key components of the area’s biodiversity.

The ancestral use of river corridors by human beings led in many cases to the reduction of the arboreal and shrubby biocoenoses to make way for herbaceous plants for the purposes of cattle rearing, using different systems of hay meadows (6510 Lowland hay meadows (Alopecurus pratensis, Sanguisorba officinalis), 6520 Mountain hay meadows) and humid meadows for grazing (6410 Molinia meadows on calcareous, peaty or clayey-silt-laden soils (Molinion caeruleae), 6420 Mediterranean tall humid herb grasslands of the Molinio-Holoschoenion). In recent decades, many river corridors have been affected by the plantation or even invasion of alien tree species (Populus spp. Eucalyptus spp. Pinus spp.), which have spread both on ancient hay and grazing meadows, and in areas occupied by humid forests and wetlands.

Additionally, it must be borne in mind that altering the balance between the water level and the transporting of sediments, caused by manmade acts (dams, channels, weirs, water diversions, bridges), also affects the characteristics of the biological communities settled in the river environment.

In this regard, since the promulgation of the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EEC, progress has been made in studying the repercussions of human activity on the state of waters in Europe and authorities have devoted a great deal of effort to identifying the risk of non-compliance with environmental objectives through the analysis of pressures and impacts on river courses and risks to them. The aim of the WFD is to achieve a good status of bodies of water, both in ecological and chemical terms.

A good ecological status depends on biological elements, but also on the hydromorphological, physical-chemical and chemical elements supporting the biological ones.

6.1. Hydromorphological alterations

The construction of dams and weirs can significantly affect the continuity of the river corridor. Upstream, a stagnant and generally deep water environment is created, which differs substantially from the biological and hydrological conditions that define a flowing water ecosystem, while downstream, the characteristics of the water surface and especially the transporting of sediments are modified. As a consequence of this imbalance in the liquid-solid flow, the river reacts in the short and medium term with morphological readjustments, such as channelling ditches, shore erosion, blocking of the riverbed, weakening of bridges or changes in the variation of rapids and wells, and so on. In turn, these transformations affect the level of the water table, the danger of flooding and the characteristics of the water surface, such as temperature and oxygenation. Such alterations will affect the associated river ecosystems and become incompatible with the development of many of the typical animal and plant species living in the river corridors, causing their disappearance from the affected stretches.

This situation can be seen clearly in the Minho basin, if the biodiversity of the river corridors of the Upper Basin (Terra Chá) and Lower Basin (Baixo Minho) is compared with that of the Middle Basin, which has a succession of large reservoirs. Before the construction of the reservoirs, species such as Nymphoides peltata, included in the Galician Catalogue of Endangered Species under the category Endangered, lived in an area of continuous distribution along the different stretches of the Minho basin, but following the construction of the reservoirs, it has disappeared from the Middle Basin, leaving the populations in the Upper and Lower Basins unconnected. A similar situation occurs with the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) or the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), which, before the construction of the large dams on the Minho, used to swim upstream almost as far as the city of Lugo, but are currently restricted to the Lower Minho. It is not just hydroelectric dams that alter the river corridor, since small weirs from the old fisheries, agricultural diversions and mills can also have a negative effect on the hydroecological regime and on the distribution and conservation status of certain species. In these cases, there is a need to evaluate actions to be carried out to ensure the coexistence of cultural, biological and ecological values, and recover the functioning of the ecological or hydrological connectivity of the river corridors.

In reservoir environments, it is essential to set everything up appropriately and sensitively, especially in the contact zone between the underwater area and the riparian zone, as well as the temporal variation of the water surface itself, to try to alleviate the loss of biodiversity caused by the hydraulic activity. Also crucial is the configuration of the banks and the areas of contact where temporary or permanent channels flow into the reservoir.

The loss of the natural state of river corridors and the decline in their ecological status are also related to different hydraulic installations, especially in those cases where the river courses are altered by channelling to rectify their route and modify their width, sometimes even sending stretches underground through tubes. The effects on a river’s dynamics resulting from such works are similar to those noted in the case of reservoirs, although the impact is worsened when the fittings on the riverbank or the riverbed are concrete or cement, since the impermeable nature of these materials reduces the level of the water table, the water exchange with alluvial aquifers and the buffering effect of the floodplain.

This kind of action alters the equilibrium of the river corridor, forcing the system to modify its processes of erosion and sedimentation, altering the longitudinal, vertical and lateral connectivity, both in the stretch directly affected by the structure and upstream and downstream of it. The power of the current and the depth of the water during floods will also be modified, often causing an intensification of the erosive processes.

6.2. Alteration of physical-chemical characteristics

Another negative factor for river corridors is determined by the surface water quality. Although in recent years a major effort has been made to provide purification to most large population centres, the physical-chemical state of surface water can still be improved in many stretches where insufficiently treated or untreated water is dumped, as well as the continual release of diffuse pollution from primary sector activities (slurry, fertilisers, etc.), which, in many cases, carries an excessive load of nutrients with direct consequences to the oxygenation of the water. In addition, energy or industrial production activities can negatively affect the pH and temperature of the water, as well as the dissolved oxygen within it. These pressures can affect the ecological status of the body of water being polluted.

6.3. Alteration of the water’s chemical characteristics

In addition to nutrient discharge and thermal pollution, industrial activities, mining operations (including those no longer active) and even some agricultural practices can alter the water’s chemical characteristics, through significant discharges of specific pollutants (which would affect the ecological status) and increases of priority substances and other pollutants above the environmental quality standards (which would affect the chemical status).

6.4. Pressures due to use

The urbanisation and industrialisation of alluvial land not only entails the destruction of natural habitats, but also, the waterproofing of the soil reduces its infiltration capacity, with a consequent increase in the quantity and speed of surface run-off. These transformations result in a rising of the flood peak and a shortening of response times, thereby increasing the risk of flooding.

Additionally, the transformation of a stretch of river into a recreational beach is an increasingly frequent occurrence. This process involves the alteration of biotopes and the destruction or reduction of natural and semi-natural biocoenoses. This is dramatic when the intended river beach is planned in a stretch of outstanding environmental value, where endemic or protected species live in the water or on the banks, and their survival in a favourable state of conservation is incompatible with the recreational activities and the maintenance of the river beach itself.

6.5. Invasive Alien Species

The ecological characteristics of river corridors, such as the fluvial dynamics of floods, create a natural system of physical disturbances which lead to their also being very susceptible to invasion by alien species. The natural hydrological regime enables the mobilisation of sediments, allowing the creation of deposits which are then available for the colonisation of plants. Meanwhile, some species use the corridors themselves as areas for expansion, thus efficiently invading other territories. different from where they settled initially.

Among the invasive species present in the river corridors of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula are those growing in areas close to the river corridors or within them (Acacia, Robinia, Pinus, Eucalyptus, Arundo, Bambusoideae, Bromus willdenowii, Lolium x boucheanum, Dactylis glomerata subsp glomerata, etc.), whose propagules have settled and developed without the need for human action, invading different areas of the river corridor, or even managing to expand into other territories.

A significant number of invasive alien plants come from plants growing in public or private gardens, as well as landscaped areas of linear infrastructure (Ailanthus altissima, Arctotheca calendula, Buddleja davidii, Cortaderia selloana, Crocosmia x crocosmiiflora, Helichrysum petiolare, Lonicera japonica, Reynoutria japonica, Sporobolus indicus, Stenotaphrum secundatum, Tradescantia fluminensis, Vinca difformis, Vinca major, Yucca gloriosa, Zantedeschia aethiopica, etc.). Again, the propagules (seeds, fruit, rhizomes) produced by individual specimens of these species cause the appearance of new populations, leading to the invasion of the river corridors. In some cases, these initial propagules are shoots obtained from the pruning of gardens (Calendula officinalis, Canna indica, Crocosmia x crocosmiiflora, Ipomoea acumina, Ipomoea purpurea, Opuntia sp., Reynoutria japonica, Salix babylonica, Yucca gloriosa, etc.) which are irregularly deposited in the river corridors or in areas near them, where they manage to settle and later expand territorially.

The presence of Alnus incana, Prunus serotina or Celtis australis is related to poorly planned and/or executed environmental restoration projects, using alien rather than native species as revegetation material. These have subsequently become naturalised and occupied new areas. This very process was the means of introduction of the aquatic oomycete Phytophthora x alni, a pathogenic agent which is affecting the alder throughout the European Union. In the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, it has been recorded as the cause of the widespread mortality of the alder (Alnus glutinosa) especially in Galicia in the last 10 years, and more recently in other north-western areas.

The presence of Alnus incana, Prunus serotina or Celtis australis is related to poorly planned and/or executed environmental restoration projects, using alien rather than native species as revegetation material. These have subsequently become naturalised and occupied new areas. This very process was the means of introduction of the aquatic oomycete Phytophthora x alni, a pathogenic agent which is affecting the alder throughout the European Union. In the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, it has been recorded as the cause of the widespread mortality of the alder (Alnus glutinosa) especially in Galicia in the last 10 years, and more recently in other north-western areas.

The aquatic environment of the river corridors of the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula is not unfamiliar with disease caused by invasive alien species, whose presence and dispersal is related to the release of plants and animals raised in domestic terrariums and aquariums, or by escape from cultivation centres, nurseries or zoos. Among this group are aquatic ferns (Azolla spp.), aquatic plants used in aquaculture (Elodea canadensis, Egeria densa, Eichhornia crassipes, Myriophyllum aquaticum), mammals from farms (Neovison vison) or zoos (Procyon lotor), plus fish (Carassius auratus, Poecilia reticulata) and reptiles (Trachemys scripta) from aquariums and terrariums. In addition, there are other species whose presence is the result of outdated sanitary control policies (Gambusia holbrooki) or recreational use (Onchorynchus mykiss, Micropercus salmoides, Procambarus clarkii) and their subsequent illegal translocation, as well as new illegal introductions in the aquatic environment.

In many cases, public activities enable the dispersal of the propagules of alien species, which are transported unintentionally on footwear and clothing, or on the hair of pets and horses (Bidens ssp., Conyza ssp., Sporobolus indicus, Stenotaphrum secundatum), and also, very significantly, on vehicles and boats, the latter of which are known to be connected to the dispersal of the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) in different basins of the Iberian Peninsula, though it has not been reported to date in the north-west. Also resulting from public activities, another way of enabling the introduction and dispersal of invasive alien species is through the continual clearing and removal of vegetation at the sides of roads and paths, which creates temporary disturbed environments that are susceptible to being easily colonised by invasive alien plants, a process that is enabled by the accidental introduction of their propagules through footwear, clothing or operators’ tools.

The general objective of the LIFE Fluvial project is to improve the state of conservation of Atlantic river corridors in the Natura 2000 Network. For this purpose, the project is carrying out a series of initiatives in several Atlantic river basins in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal), where various threat factors are causing the deterioration and fragmentation of the river corridor habitats. These threats affect the quality and continuity of the hygrophilous forests, the main habitat on which the project is focused (91E0* Alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior), considered a priority and a key element in maintaining the composition, structure and functionality of the river corridors. In addition, the project has another habitat in its objectives: 9230 Galicio-Portuguese oak woods with Quercus robur and Quercus pyrenaica, since these have continuity with habitat type 91E0*.

The general objective of the LIFE Fluvial project is to improve the state of conservation of Atlantic river corridors in the Natura 2000 Network. For this purpose, the project is carrying out a series of initiatives in several Atlantic river basins in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal), where various threat factors are causing the deterioration and fragmentation of the river corridor habitats. These threats affect the quality and continuity of the hygrophilous forests, the main habitat on which the project is focused (91E0* Alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior), considered a priority and a key element in maintaining the composition, structure and functionality of the river corridors. In addition, the project has another habitat in its objectives: 9230 Galicio-Portuguese oak woods with Quercus robur and Quercus pyrenaica, since these have continuity with habitat type 91E0*.

To achieve this objective, the project proposes the development of a transnational model of sustainable management for river corridors to improve their conservation status, by restoring the composition, structure and functionality of their habitat types, improving connectivity and reducing their fragmentation. At the same time, the project intends to contribute to knowledge of the river corridors, on the part of society, and the problems which affect them, by presenting this information to public opinion-makers, riverside populations, different civic organisations and the managers of the territory.

The main tenets of this strategy are the following:

- Control of alien and invasive flora

- Improvement of the phytosanitary status of the river corridors, through the partial removal of trees infected with Phythophthora.

- Dissemination and awareness-raising of the natural value, the socio-economic benefits and ecosystem services provided by river corridors

- Improvement of the education and technical training of people involved in the management and conservation of the river corridors

Based on the above, the project is structured around the following action:

- Preparatory action. Preliminary assessment of the areas for action, common indicators for monitoring, technical planning of action, expropriation plan.

- Land acquisition. Acquisition, through expropriation, of land adjacent to the fluvial-estuarine riverbank in the municipality of Ribadeo (Galicia), in order to naturalise these lands through the destruction of eucalyptus plantations and the restoration of natural habitats.

- Conservation action. 8 conservation initiatives have been defined in 9 Natura 2000 sites in Spain and Portugal, distributed along the upper, middle and lower reaches of five river basins, to improve the state of conservation of river corridor habitats, mainly of type 91E0*. The tasks included in these initiatives are: control of invasive species, removal of dead alders, restoration of natural vegetation cover.

- Monitoring action. Follow-up action to measure the impact of the project on the target habitats, to assess the socio-economic impact of the project, to assess the impact of the project on ecosystem functions, as well as to analyse the progress of the project.

- Public awareness-raising and dissemination of results. This action includes a Communications Plan; design, creation and implementation of informative, didactic and awareness-raising materials and equipment; design and implementation of an awareness-raising and dissemination programme; publication of an informative electronic newsletter; launch of a website and the establishment of relations with other projects of a similar nature.

- Project management. Action related to the process of managing and coordinating the project.